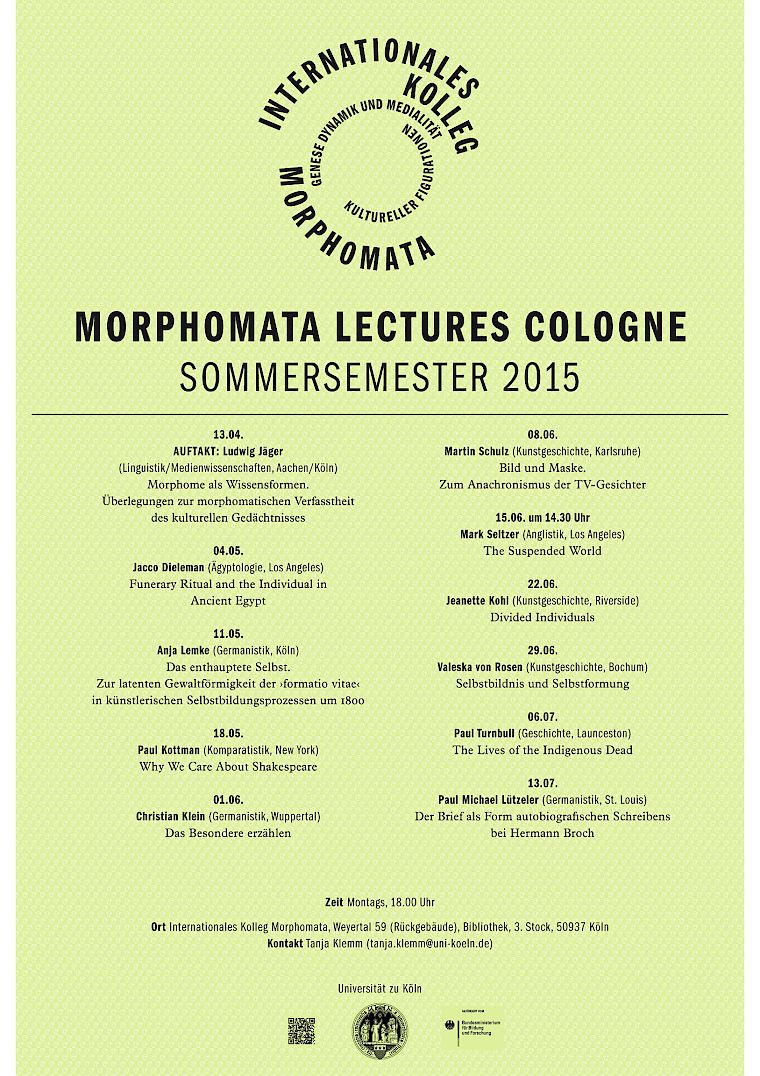

In this lecture, I will speak briefly about three main strands of inquiry within this project, which is tentatively entitled the Lives of the Indigenous Dead. The first strand explores how the bodily remains of indigenous peoples acquired by anatomists and (generally medically trained) anthropologists during the first half of the long nineteenth century often acquired what in effect were new life-histories The second strand focuses on the how medico-scientific researchers active between 1860 and 1930 imagined the lives of paleolithic Europeans, and how the typological life-histories they fashioned proved a fertile source of inspiration for fictional and visual representations of archaic homo sapiens and earlier Hominids. Here, I am particularly interested in how scientific and also popular reconstructions of the lives of palaeolithic Europeans drew on ethnographic reportage of indigenous peoples.

Historians of anthropology have drawn attention to how comparative cranial analysis of Australian and fossilised cranial bones of Neanderthal led early Darwinian anatomists to conclude that Indigenous Australians still living traditionally in the remote central and northern regions of the continent were a primitive human type which had become trapped in evolutionary stasis. Within the European imaginary, Australian and other indigenous peoples who likewise lived largely by hunting and foraging were imagined to be, in Tony Bennett's memorable phrase, at 'evolutionary ground zero.' What has so far received relatively little attention, however, is the selective use of ethnographic documentation of the life-ways and culture of indigenous peoples - notably Aboriginal Australians, Khoi-San peoples, and the Qawasqar peoples of Tierra del Fuego - to reconstruct the life-histories of Europe's palaeolithic inhabitants.

This body of ethnographic reportage work was the product of interactions between colonially based observers of indigenous peoples during, or soon after, these peoples experienced the violent expropriation of their ancestral lands and loss of traditional life-ways. It was generally undertaken in the erroneous belief that its subjects were innately incapable of adapting to life in European settler society and thus were doomed to extinction.

Ethnographic pessimism also licensed the elegiac portrayal of indigenous men and women as the last of their kind, tribe or race. Literary scholars and art historians have drawn attention to the vanishment of the native having been a common theme within poetry, drama and the visual arts in European settler societies from the 1820s onwards. They have noted, moreover, that these sentimental portrayals of indigenous life often knowingly provoked moral unease that the price of transplanting European civilisation to the Americas, southern Africa and Australasia was the doom of these continents' first peoples. This was especially so in respect of Tasmanian Aboriginal people, who, as is well known, were burdened with supposedly being the first indigenous race to suffer extinction because of their alleged innate inability to benefit from colonial tutelage.

The documentation of indigenous life-ways and culture occurred at a time of intense nationalism in Europe, which saw the promotion by political elites of national states, and growing national rivalries. A second strand of this project is motivated by curiosity as to the extent to which colonial ethnography and artistic portrayals of indigenous people as the 'last of their race' contributed to metropolitan cultural investment in the idea that the natural history of humankind was fundamentally characterised by social and moral progress having been achieved through racial struggle and supersession.

Finally, I will briefly say something about the third strand of this project, which is closely connected to my ongoing interest in the contemporary phenomenon of the repatriation of indigenous ancestral remains from western scientific institutions. In a sense, the indigenous dead whose remains became objects of scientific curiosity never died. Indigenous communities do not regard those of their ancestral remains that are now being returned by western scientific institutions as bereft of spiritual presence. The communities in question believe that death sees a person's spirit take leave of the body, but only after the successful performance funerary rituals, and so long as their remains lay undisturbed within a specific location in ancestral country. If the required rituals do not take place, or bodily remains are removed from burial places, the spirits of the dead suffer torment and may directly or indirectly do serious harm to the living. Hence indigenous people approach the return of ancestral remains as a profoundly serious and potentially dangerous obligation, presuming that they are infused with ancestral spirits wanting the peace that only burial in accordance with tradition can give them.

(Der Vortrag wird auf englisch gehalten)

Der Vortrag ist öffentlich, alle Interessenten sind herzlich eingeladen!